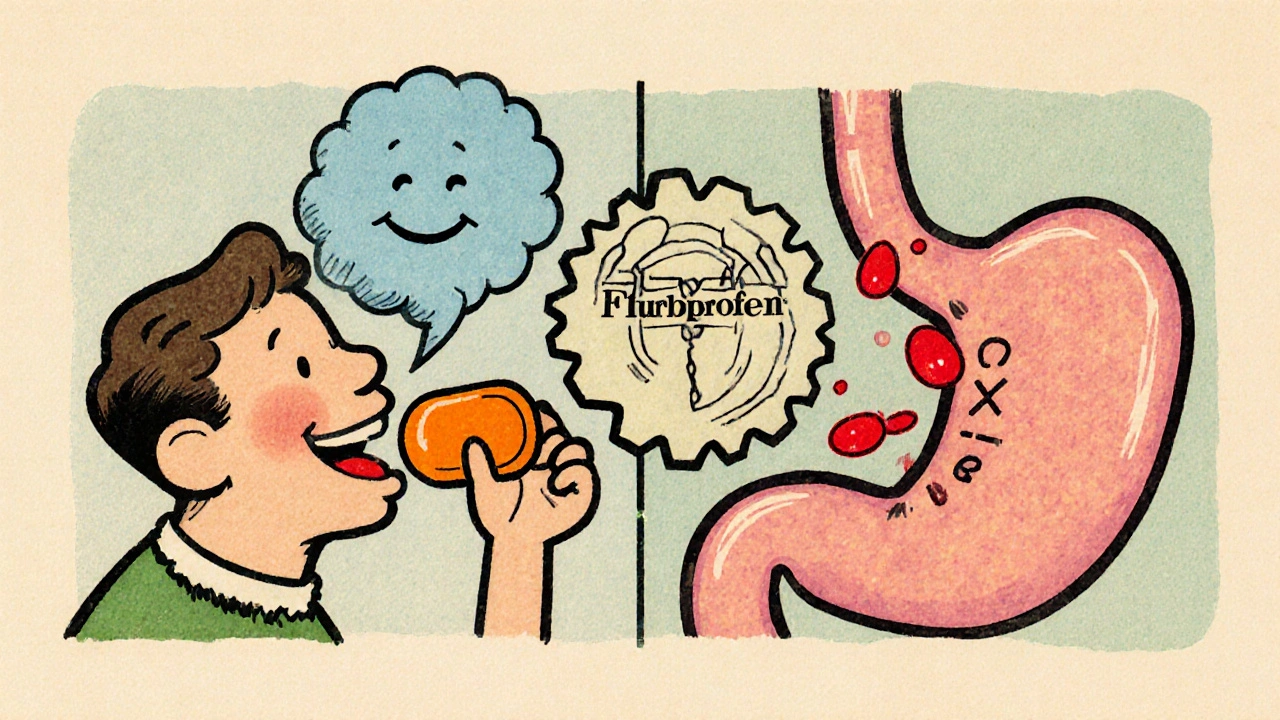

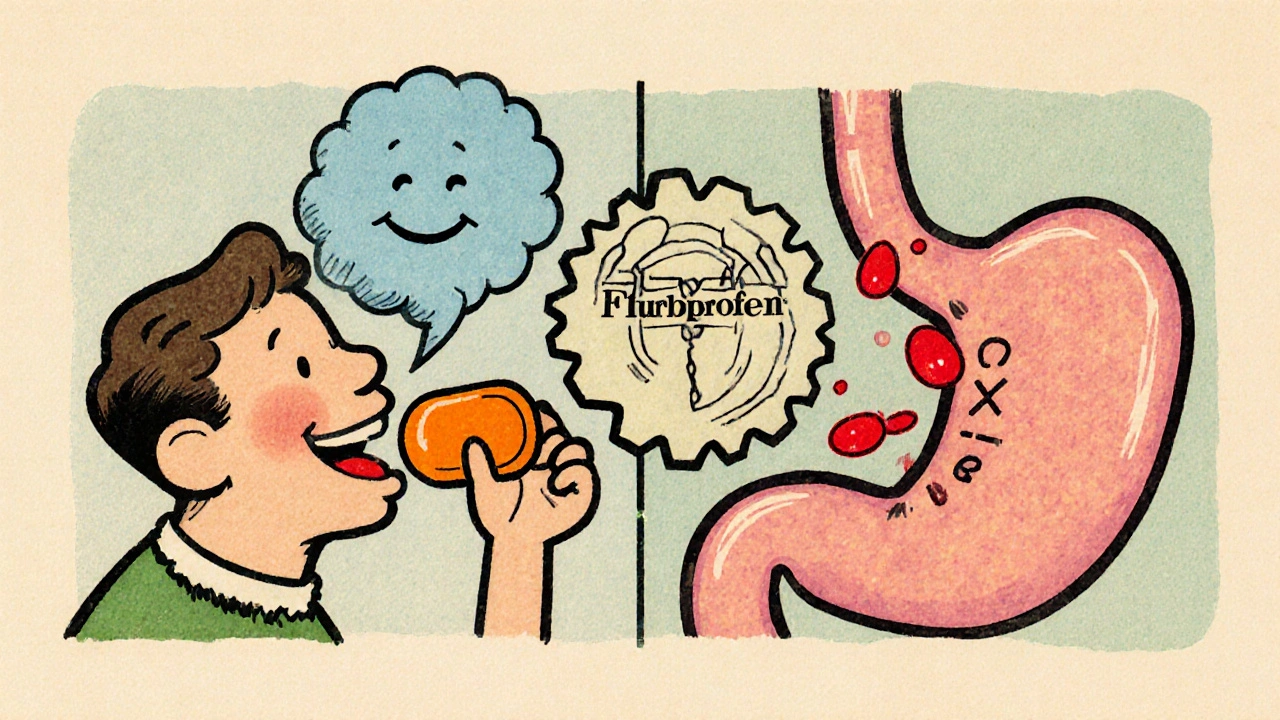

Flurbiprofen & Stomach Ulcers: Risks, Symptoms, and Safe Use

Learn how flurbiprofen can cause stomach ulcers, recognize warning signs, and use safe strategies to protect your gut while staying pain‑free.

When talking about NSAID ulcer risk, the chance that taking non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs leads to stomach ulceration or bleeding. Also known as NSAID‑related ulcer risk, it matters to anyone using pain relievers regularly. Right alongside this risk, NSAIDs, a class of drugs that reduce inflammation and pain by blocking cyclo‑oxygenase enzymes are the most common trigger.

Why do these everyday meds sometimes turn into a stomach problem? The answer lies in how NSAIDs interfere with the protective lining of the gut. By inhibiting COX‑1, they cut down prostaglandin production, which normally helps keep the stomach lining moist and resistant to acid. Without that shield, the acidic environment can erode the mucosa and start a peptic ulcer, a sore that forms on the stomach or duodenal wall due to acid damage. In short, NSAID ulcer risk is a direct result of that lost protection.

Not every user will develop an ulcer, but several factors tip the scales. Age over 60, a history of ulcer disease, concurrent use of steroids or anticoagulants, and high‑dose or long‑term NSAID therapy all increase vulnerability. When ulcers do form, they can bleed, leading to what doctors call gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding—a serious complication that may require hospitalization. Recognizing these risk amplifiers helps you make smarter choices about pain management.

One of the most effective ways to protect the stomach is adding a medication that reduces acid exposure. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), drugs that block the stomach’s acid‑producing pumps, dramatically lower ulcer and bleed rates in NSAID users. Common PPIs include omeprazole, esomeprazole, and pantoprazole. When prescribed alongside an NSAID, they act like a shield, keeping the lining safe while the pain reliever does its job.

Another option is switching to a COX‑2‑selective NSAID, which targets the inflammation‑related enzyme while sparing COX‑1. This design reduces the impact on the stomach’s protective prostaglandins. However, COX‑2 blockers have their own cardiovascular concerns, so they’re not a universal fix. Discussing your health profile with a doctor is crucial before making any switch.

Lifestyle tweaks also matter. Taking NSAIDs with food, avoiding alcohol, and quitting smoking can all lessen irritation. If you need regular pain control, consider alternating NSAIDs with acetaminophen, which doesn’t carry the same ulcer risk. Monitoring for warning signs—such as dark stools, abdominal pain, or unexplained fatigue—lets you catch problems early before they become emergencies.

In practice, managing gastrointestinal bleeding, the loss of blood from the digestive tract often caused by ulcer erosion involves stopping the offending NSAID, starting a PPI, and sometimes using endoscopic techniques to seal the bleed. The goal is to halt blood loss, heal the ulcer, and prevent recurrence.

Overall, understanding how NSAID use, ulcer formation, and protective therapies intersect empowers you to stay ahead of stomach problems. Below, you’ll find a curated set of articles that dive deeper into each piece—whether you’re looking for detailed drug comparisons, tips on safe NSAID use, or guidance on choosing the right ulcer‑prevention plan. Use them as a road map to keep pain relief effective without compromising your gut health.

Learn how flurbiprofen can cause stomach ulcers, recognize warning signs, and use safe strategies to protect your gut while staying pain‑free.