When a generic drug hits the shelf, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do we know that for sure? The answer lies in bioequivalence studies-clinical trials that compare how quickly and how much of a drug enters the bloodstream. For decades, these studies were done almost exclusively on young, healthy men. That’s changing. Today, regulators and scientists are pushing for study designs that reflect real-world patients, especially when it comes to age and sex. Ignoring these factors doesn’t just raise ethical concerns-it can lead to real risks in how drugs work for women, older adults, and other groups.

Why Bioequivalence Studies Used to Ignore Women and Older Adults

For years, the default for bioequivalence trials was simple: enroll young men. Why? Because they were seen as the most predictable group. Their bodies didn’t fluctuate with menstrual cycles. They didn’t have age-related changes in liver or kidney function. And they were easier to recruit. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA didn’t explicitly require diversity-they just didn’t demand it. So sponsors followed the path of least resistance. But this approach ignored science. Studies have shown that men and women often process drugs differently. Women tend to have higher body fat percentages, lower muscle mass, and different levels of enzymes that break down medications. For example, a 2023 study from the University of Toronto found that 37% of commonly tested drugs are cleared 15-22% faster in men than in women. That doesn’t mean the drug fails-it means the dose might need to be adjusted. If a generic version is only tested in men, and women end up taking it, they could get too much or too little of the active ingredient. The same issue applies to older adults. As people age, their liver and kidneys don’t work as efficiently. Blood flow slows. Stomach acid changes. All of this affects how a drug is absorbed and eliminated. Yet, until recently, most bioequivalence studies excluded anyone over 50 or 55. That’s a problem when drugs like statins, blood pressure pills, or levothyroxine are taken mostly by people over 65.How Regulatory Agencies Are Changing the Rules

The tide turned in 2013 when the FDA first started urging sponsors to include more women in bioequivalence studies. But it wasn’t until May 2023 that they made it official. In their draft guidance, the FDA now says: “If a drug product is intended for use in both sexes, the applicant should include similar proportions of males and females in the study.” That’s not a suggestion anymore-it’s a requirement unless you can scientifically prove otherwise. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has been more cautious. Their 2010 guideline says subjects “could belong to either sex,” but doesn’t require balance. That’s still the case. However, they’re reviewing their rules in 2024, and pressure is building to align with the FDA’s approach. Brazil’s ANVISA is already stricter. They require exactly equal numbers of men and women, ages 18 to 50, with no smoking and BMI within normal range. Canada accepts 18 to 55, but still leans toward healthy volunteers. The key difference? The FDA now wants studies to reflect the actual patient population. The EMA still prioritizes sensitivity-can you detect a difference between two formulations? The FDA asks: Will this drug work the same for the people who will actually use it?What the Numbers Don’t Tell You

Even with these new rules, real-world data tells a troubling story. Between 2015 and 2020, the FDA analyzed over 1,200 generic drug applications. Only 38% of them had between 40% and 60% female participants. The median? Just 32%. That’s far below what you’d expect. Take levothyroxine, a thyroid medication used by 63% women. Yet, most bioequivalence studies for it enroll fewer than 25% women. Why? Recruitment. Women are less likely to join clinical trials. They have caregiving responsibilities. They’re more cautious about taking experimental drugs. Sites report it takes 40% longer to enroll gender-balanced studies. And when you’re under pressure to get a generic to market fast, it’s tempting to stick with the old model. But that’s where the risk hides. In one study from 2017, a small trial with only 14 participants showed a drug was bioinequivalent in men but fine in women. The difference wasn’t real-it was statistical noise. A follow-up study with 36 participants showed no difference at all. Small studies amplify random variation. That’s why regulators now recommend enrolling at least 24 to 36 people, not the bare minimum of 12. More participants mean more reliable data-and less chance of false alarms.

How to Design a Better Bioequivalence Study

If you’re designing or reviewing a bioequivalence study, here’s what you need to do:- Match the target population. If the drug is used mostly by women, enroll mostly women. If it’s for older adults with kidney issues, include them-don’t exclude them just because they’re “not healthy.”

- Stratify by sex. Randomize participants so that each group (test and reference) has the same number of men and women. This prevents one group from being skewed.

- Plan for subgroup analysis. Don’t just look at the overall result. Analyze pharmacokinetic data separately for men and women. Are there differences in absorption? Peak concentration? Half-life? If so, document them.

- Don’t assume age doesn’t matter. If the drug is for seniors, include at least 20% of participants aged 60 or older. If you exclude them, you need a solid scientific reason.

- Track more than just AUC and Cmax. Look at variability. Women often show higher variability in drug levels. That doesn’t mean the drug is bad-it means you need a larger sample size to detect true differences.

The Hidden Cost of Getting It Wrong

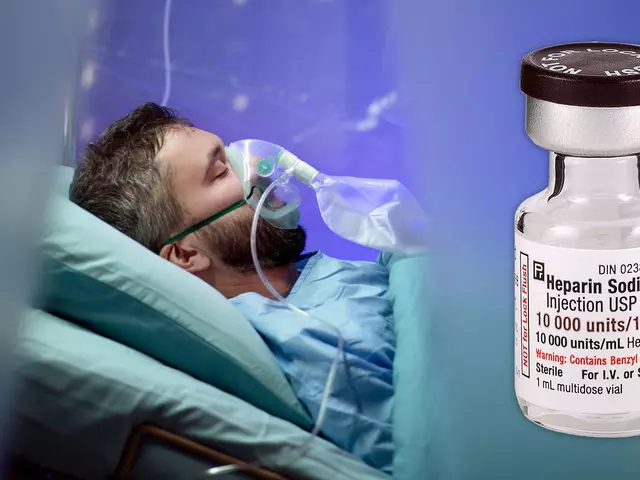

Underrepresenting women and older adults isn’t just a scientific flaw-it’s a safety issue. In 2018, a generic version of a blood thinner was approved based on a study with 90% men. After launch, women reported more bleeding events. The manufacturer had to issue a warning. The FDA later found the generic had a slightly different release profile in women, which wasn’t caught because the study didn’t test them. There’s also a financial risk. If your study doesn’t meet FDA expectations, they’ll issue a Complete Response Letter. That means delays. More testing. More cost. And you might have to redo the entire trial. In 2022, Lachman Consultants reported that 18% of ANDA submissions were rejected or delayed due to inadequate population representation. On the flip side, companies that get it right benefit. The FDA now gives priority review to applications that include diverse populations. That means faster approval. And patients trust brands that show they care about real-world use.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

The future is clear: bioequivalence studies must reflect the people who take the drugs. The FDA’s 2023 guidance is the biggest step yet. Other agencies will follow. The EMA’s review in 2024 could bring Europe into line. ANVISA and Health Canada are already moving forward. Researchers are also pushing for sex-specific bioequivalence criteria, especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin, lithium, or digoxin. A drug that’s safe for men might be toxic for women if the dose isn’t adjusted. We’re not there yet, but the data is piling up. The next big challenge? Including people with chronic conditions. Right now, most studies require “healthy volunteers.” But if you’re prescribing a drug to someone with diabetes, heart failure, or liver disease, shouldn’t the bioequivalence data reflect that? The FDA allows it under certain conditions, but few sponsors take advantage. That’s the next frontier.What You Should Know as a Patient

You don’t need to understand pharmacokinetics to protect yourself. But you should know this: if you’re a woman or over 60 and taking a generic drug, your experience might be different from what the study showed. That doesn’t mean the drug is unsafe. But if you notice side effects that others don’t have-or if the drug doesn’t seem to work as well-talk to your doctor. Ask: “Was this generic tested on people like me?” Pharmacists can help too. They have access to drug databases that show which generics were tested in which populations. If you’re concerned, ask for a brand-name version-or ask your prescriber to check the bioequivalence data.Frequently Asked Questions

Why are bioequivalence studies often done only on men?

Historically, studies used young, healthy men because they were seen as the most predictable group. Their hormone levels are stable, and they don’t have age-related changes in metabolism. This made it easier to detect small differences between drug formulations. But this approach ignored real-world differences in how men and women process drugs, leading to gaps in safety and effectiveness data.

Does the FDA require equal numbers of men and women in bioequivalence studies?

Yes, as of the May 2023 draft guidance, the FDA requires similar proportions of males and females if the drug is intended for both sexes. Sponsors must justify any deviation from this 50:50 target. This is a major shift from past guidance, which only encouraged diversity without mandating it.

Can older adults be included in bioequivalence studies?

Yes, and they should be-if the drug is meant for older patients. The FDA now requires that studies include subjects aged 60 or older when the drug targets that population. If they’re excluded, the sponsor must provide a strong scientific reason. Many studies still skip older adults, but regulators are increasingly rejecting applications that don’t reflect real-world use.

Are women more likely to have side effects from generic drugs?

Not necessarily-but they’re more likely to experience side effects if the drug wasn’t tested on them. Women often metabolize drugs differently due to body composition, hormone levels, and enzyme activity. If a generic is only tested in men, the dose may be too high or too low for women, leading to unexpected reactions. This isn’t about gender-it’s about data gaps.

How do I know if a generic drug was tested on people like me?

You can ask your pharmacist or doctor to check the FDA’s Orange Book or the drug’s approval package. These documents list the demographics of the bioequivalence study participants. If the study included mostly men under 50 and you’re a woman over 65, you may want to discuss alternatives with your provider. Transparency is improving, but it’s still not always easy to find.

so i read this and now i think the fda is just letting big pharma slip in fake generics through back doors... they say they want diversity but every study i see still has like 10 guys in their 20s who smoke weed and drink protein shakes... its all a scam. they dont care if your grandma dies from a pill that was only tested on college dudes. #conspiracy

How utterly predictable. The FDA’s latest ‘guidance’ is nothing but performative wokeness dressed up as science. If you want real data, test on healthy young adults-their physiology is consistent. Introducing variability from sex and age only muddies the results. This isn’t progress-it’s ideology masquerading as regulatory rigor.

Oh please. We’re now in the era where bioequivalence is decided by demographic quotas instead of pharmacokinetic integrity. Women don’t ‘process drugs differently’-they metabolize them *differently*. And that’s not a bug, it’s a feature of human biology. But instead of designing studies to account for that, we’re just throwing bodies into the mix like a diversity bingo card. The real failure? Not understanding *why* the differences exist.

This is actually really important and I’m so glad someone’s talking about it. 💪 If you’re a woman over 60 and your generic isn’t working like it used to-you’re not imagining it. Talk to your pharmacist. Ask for the study data. You deserve to know if you’re being treated like a lab rat from 1998. We can do better.

Oh great. Now we’re going to have 12 different versions of the same pill because someone’s afraid a woman might have a ‘reaction.’ Next thing you know, we’ll need a separate generic for left-handed people who eat gluten-free. This is why America is falling apart.

You think this is bad? Wait till you find out the EMA’s still letting companies use 12-year-old male undergrads as ‘representative’ subjects. It’s not just negligence-it’s criminal. And if you’re a woman over 50 taking levothyroxine and you’re not seeing results, it’s because your pill was tested on a guy who bench-presses 200 lbs and hasn’t slept in 72 hours. That’s not science. That’s corporate negligence.

they just want to make us all sick so they can sell more drugs. why else would they test on men only? it’s a plot. i saw it on a youtube video. the pills are laced with microchips and the women get the wrong dose on purpose. i know someone who took a generic and her hair fell out. they didn’t test it on her. she’s 62. they don’t care.

The pharmacokinetic variability across sex and age cohorts is not merely a confounder-it’s a critical parameter that undermines the validity of the 90% CI threshold when applied homogenously. The current paradigm assumes log-normality and homoscedasticity across strata, which is empirically invalid. We need population PK/PD modeling with stratified randomization, not tokenistic enrollment.

It’s not about politics. It’s about precision medicine. If a drug behaves differently in women or older adults, and we don’t test it on them, we’re not just being lazy-we’re putting lives at risk. The science is clear: body composition, enzyme activity, organ function-all change with age and sex. Ignoring that isn’t ‘efficient.’ It’s dangerous. And frankly, it’s disrespectful to the people who rely on these drugs every day.

man, i had no idea this was even a thing. my mom’s on levothyroxine and she’s always saying the generic ‘feels off.’ i thought she was just being dramatic. now i get it. if your pill was only tested on guys half your age, it’s no wonder it doesn’t feel right. maybe it’s time to ask your doc for the real data. you’ve got a right to know.

The FDA’s ‘similar proportions’ language is deliberately vague. What does ‘similar’ mean? 45/55? 40/60? That’s not a standard-it’s a loophole. And the fact that only 38% of studies hit that arbitrary 40–60% female range proves this is all theater. Real science doesn’t need PR spin. It needs hard numbers and stratified analysis. What we’re getting is compliance theater.

THIS IS WHY WE CAN’T HAVE NICE THINGS 😭 The FDA is turning medicine into a diversity spreadsheet. They’re not testing drugs anymore-they’re testing whether you’re ‘representative.’ My uncle took a generic heart med and had a stroke. Turns out the study had 2 women. 2. Out of 24. 😭😭😭 We’re killing people with woke math.

They exclude older adults because they’re ‘too complex.’ But then prescribe the drug to them anyway. That’s not science. That’s fraud. And the worst part? No one gets punished.

They’re hiding the truth. The real reason they don’t test on women and older people? Because the drug might not work. And if it doesn’t work, the company loses billions. So they lie. They lie to regulators. They lie to doctors. They lie to us. And people die. And no one goes to jail.

While the empirical rationale for demographic inclusion in bioequivalence protocols is methodologically sound, the operational constraints-recruitment latency, increased variance, and cost escalation-remain non-trivial. The regulatory imperative must be balanced against the practical feasibility of achieving statistical power under real-world constraints. A one-size-fits-all mandate may yield unintended consequences in market access.