Every time a pharmacist swaps a brand-name drug for a generic, they’re making a decision with real legal consequences. It’s not just about saving money-it’s about protecting patients, avoiding lawsuits, and staying compliant in a patchwork of state laws that change faster than most pharmacists can keep up. In 2025, with over 90% of prescriptions filled as generics, this isn’t a rare edge case. It’s daily practice. And the risk? It’s real.

Why Generic Substitution Isn’t Just a Cost-Saving Move

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system billions every year. Between 2009 and 2018, they saved $1.67 trillion. That’s huge. But behind that number is a legal minefield. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act made generics possible by letting manufacturers skip expensive clinical trials, as long as they proved their drug was bioequivalent to the brand. That means the generic delivers 80-125% of the active ingredient in the same way. Sounds simple, right? But bioequivalence doesn’t guarantee therapeutic equivalence-especially for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index. Think warfarin, levothyroxine, or seizure meds like phenytoin. These drugs need blood levels to stay within a tiny window. Too little? The patient seizes or develops clots. Too much? They bleed internally or suffer neurological damage. A 2017 study in Epilepsy & Behavior found that 18.3% of patients had therapeutic failure after switching to a generic antiepileptic. That’s not a glitch. That’s a pattern. And here’s the catch: if something goes wrong, the pharmacist can be the one held responsible-even if the drug was approved by the FDA and met all technical standards.The Legal Trap: Who’s Liable When Things Go Wrong?

The Supreme Court’s 2011 decision in PLIVA v. Mensing changed everything. It ruled that generic manufacturers can’t be sued under state law for failing to update warning labels. Why? Because federal law forces them to use the exact same label as the brand-name drug. They can’t add a warning about a newly discovered side effect, even if they know it’s happening. That leaves patients with nowhere to turn. And it leaves pharmacists in a tough spot. If a patient has a bad reaction after a generic switch, and the label didn’t warn them, who’s at fault? The pharmacist? The doctor? The manufacturer? The system says no one. State laws make it worse. In 27 states, pharmacists are required to substitute generics unless the doctor says no. In 23 others, substitution is optional. Only 18 states require the pharmacist to directly notify the patient-beyond just putting a sticker on the bottle. And in 23 states, there’s no legal protection for pharmacists: if a patient sues, you’re on the hook for the same damages as if you’d dispensed the brand. Connecticut and Massachusetts have seen 27% more malpractice claims related to substitution than states like California or Texas, where laws clearly shield pharmacists from extra liability. That’s not coincidence. It’s policy.High-Risk Drugs: What Pharmacists Need to Know

Not all generics are created equal. Some drugs are safe to swap. Others are not. The American Epilepsy Society flagged antiepileptics as high-risk in 2018, noting a 7.9% increase in seizure risk after generic switches. The FDA’s own data shows substitution rates for these drugs hover around 37%-far lower than for statins (98%) or blood pressure meds (82%). Why? Because pharmacists know the stakes. Here are the drugs you should treat like live wires:- Levothyroxine (for hypothyroidism)

- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproate (antiepileptics)

- Lithium (for bipolar disorder)

- Cyclosporine (organ transplant)

How to Protect Yourself: 7 Practical Steps

You can’t control the law. But you can control your process. Here’s how to reduce your risk-starting today.- Know your state’s rules. Laws change every year. Use the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy’s Compendium of State Pharmacy Laws. Don’t rely on memory. Bookmark it. Print it.

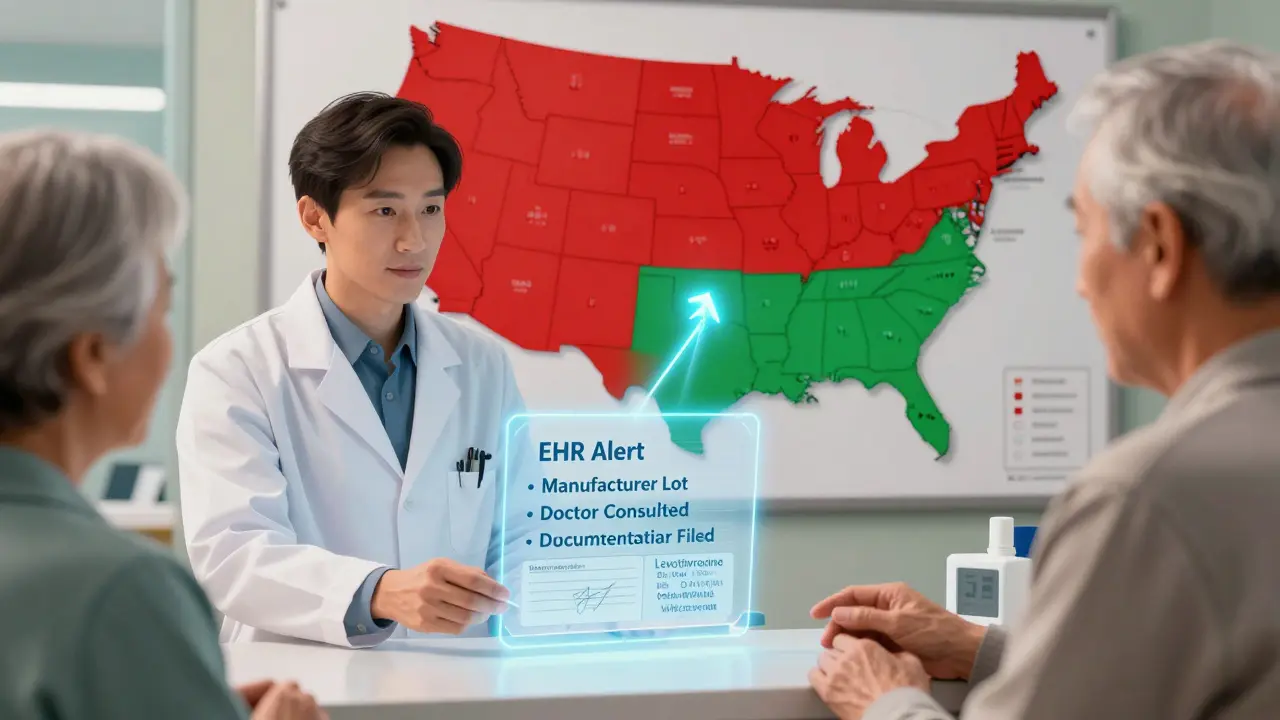

- Flag high-risk drugs in your system. Set up EHR alerts for levothyroxine, warfarin, and antiepileptics. When a generic is selected, your system should pop up: “Narrow therapeutic index. Confirm patient consent.”

- Get written consent. Even if your state doesn’t require it, do it anyway. Use a simple form: “I understand my prescription has been switched to a generic. I’ve been told this may affect my condition. I accept this substitution.” Have the patient sign and date it. Keep it in the file.

- Communicate with prescribers. If a patient has a history of instability after a switch, call the doctor. Say: “I noticed this patient had issues with a prior generic switch. Would you prefer we stick with brand?” Most doctors appreciate the heads-up.

- Track every substitution. Record the brand name, generic name, manufacturer, and lot number. If a problem arises later, you’ll need this for traceability. Don’t skip this step.

- Do an annual liability risk assessment. Use the 27-point checklist from the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. It covers documentation, training, and communication gaps most pharmacies miss.

- Get supplemental malpractice insurance. Standard policies don’t always cover substitution-related claims. Look for one that explicitly includes generic drug liability. Premiums are up 18% since 2011, but the cost of one lawsuit? Far higher.

What Patients Don’t Know-And Why It Matters

A 2021 survey by the Patient Advocacy Foundation found 41% of patients didn’t know their prescription had been switched until they felt worse. That’s not negligence. That’s a system failure. Patients assume their pharmacist is protecting them. They don’t realize that in some states, the pharmacist isn’t even required to tell them. And here’s the irony: 82% of patients on GoodRx report being happy with generic substitutions for common drugs like metformin or lisinopril. They save $327 a year. No problems. But for the 18% who experience side effects, the confusion is devastating. They blame their doctor. Their pharmacist. Their body. No one tells them: “This is a legal loophole, not your fault.”

The Bigger Picture: Where Is This Headed?

In 2023, 11 states introduced bills to fix the liability gap. California’s SB 452 and New York’s A.7321 propose a shared responsibility model: brand-name manufacturers must update their labels within 30 days of new safety data, and generic makers must adopt those updates within 60. It’s not perfect-but it’s progress. The FDA’s 2023 pilot program for label changes has approved 68% of requests, but only 12% came from generic manufacturers. Why? Because they’re still legally blocked from initiating changes on their own. The long-term solution? A centralized, standardized labeling system-what Harvard’s Dr. Aaron Kesselheim calls “consensus labeling.” Imagine one label for all versions of levothyroxine, updated by an independent body based on real-world data. That would remove the legal ambiguity. It would protect patients. And it would protect pharmacists. Until then, your best defense is your process. Document everything. Communicate clearly. Know your state’s laws. And when in doubt-don’t substitute.Frequently Asked Questions

Can a pharmacist be sued for substituting a generic drug?

Yes. While generic manufacturers are protected from lawsuits due to federal preemption, pharmacists can be held liable under state law if they fail to follow substitution rules, don’t obtain required consent, or substitute a high-risk drug without proper documentation. Liability depends on state law, but courts have upheld claims against pharmacists when substitution led to patient harm and proper protocols weren’t followed.

Which states require pharmacists to notify patients about generic substitution?

Eighteen states and Washington, D.C. require pharmacists to directly notify patients about generic substitution beyond just labeling. These include California, New York, Florida, and Illinois. In these states, notification must be clear, verbal or written, and separate from the pharmacy label. Failure to notify can lead to malpractice claims, even if the substitution itself was legal.

Are all generic drugs safe to substitute?

No. Generic drugs are required to be bioequivalent, but not always therapeutically equivalent-especially for narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, and antiepileptics. Studies show increased risk of adverse events after substitution for these drugs. Pharmacists should avoid substitution for these unless the patient is stable, fully informed, and consents in writing.

What should I do if a patient reports side effects after a generic switch?

Immediately document the report, check the lot number and manufacturer of the generic dispensed, and contact the prescriber. Offer to switch back to the brand or try a different generic manufacturer. In high-risk cases, consider testing blood levels (e.g., TSH for levothyroxine, INR for warfarin). Never dismiss the concern-even if the drug is labeled “bioequivalent.” Patient reports are often the first sign of a real problem.

Does my standard pharmacist liability insurance cover generic substitution claims?

Not always. Many standard policies exclude or limit coverage for substitution-related claims. Check your policy wording carefully. Look for explicit language covering “generic drug substitution liability.” If it’s not there, consider upgrading to a policy that does. Premiums have increased by 18% since 2011, but the cost of defending a single lawsuit can exceed $200,000.

Can I refuse to substitute a generic drug even if the law allows it?

Yes. Even in states where substitution is mandatory, pharmacists can refuse if they believe it poses a risk to patient safety. Many pharmacists in high-risk cases (e.g., antiepileptics) refuse substitution despite state laws permitting it. Document your reasoning clearly: “Substitution refused due to patient history of instability with prior generic switch.” This protects you legally and ethically.

Look, I get it-generic substitution saves pennies, but when your TSH spikes from 2.1 to 12.8 because some pharmacy swapped levothyroxine without telling you, it’s not a cost-saving measure. It’s a fucking liability cascade. The FDA’s bioequivalence standard is a joke for narrow-therapeutic-index drugs. We’re playing Russian roulette with patients’ neurology and endocrine systems, and pharmacists are the ones getting sued when the chamber fires. Stop pretending this is about efficiency. It’s about corporate greed dressed up as public health.

Every substitution should require a signed, witnessed consent form-especially for levothyroxine, warfarin, and antiepileptics. Not a sticker. Not a checkbox. A signature. And the prescriber should be notified. It’s not just best practice-it’s basic human dignity.

So let me get this straight: a pharmacist can be sued for switching a drug, but the company that made the generic can’t be held accountable for a faulty label? That’s not a legal system. That’s a corporate loophole with a badge. And now we’re supposed to thank the pharmacist for not getting us killed? I’m not impressed. I’m furious.

Bro. I’ve been a pharmacy tech for 12 years. I’ve seen people go from stable to seizing because some generic switched their phenytoin. We’re not talking about a 5-cent difference here. We’re talking about people losing their jobs, their licenses, their lives. And yeah, I’ve printed consent forms. I’ve flagged EHR alerts. I’ve called docs. I’ve lost sleep over this. You don’t need a law degree to know this is wrong. You just need a heart.

Man, this hits hard 😔 I’m from India, and here generics are EVERYWHERE-no regulation, no tracking, no consent. We don’t even have EHRs in most clinics. The idea that a pharmacist in the U.S. has to navigate this maze… it’s both impressive and terrifying. I hope your system fixes this. For everyone. 🙏

So… we’re telling pharmacists to be doctors, lawyers, and patient advocates… while the system gives them zero legal backup? Classic. 🤡

Step 1: Know your state laws. Step 2: Flag high-risk drugs. Step 3: Get consent. Step 4: Document everything. Step 5: Get better insurance. That’s not ‘extra work.’ That’s your job. If you’re not doing this, you’re not a pharmacist-you’re a pill dispenser. And the system’s already punishing people who cut corners. Don’t be one of them.

Let me tell you what’s really going on here. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know this, but the real reason generics are pushed so hard is because the brand-name companies have already maxed out their patent profits. So they hand off the dangerous, high-risk drugs to the generics-where the liability is buried under state law, and the manufacturer is legally shielded. The pharmacist? The perfect fall guy. The FDA? Complicit. The patient? A statistic. And we’re supposed to be grateful because it’s ‘cheaper’? No. No. No. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a Ponzi scheme with stethoscopes.

And don’t even get me started on the excipients. You think it’s just ‘inactive ingredients’? Try lactose intolerance triggering a seizure in someone on phenytoin because the generic used a different filler. Or a dye causing anaphylaxis because the brand used a different coloring agent. The FDA doesn’t require disclosure of those. But if you’re the pharmacist who filled it? You’re on the hook.

I’ve seen it. I’ve documented it. I’ve cried in the back room after a patient had to be intubated because we switched their levothyroxine without telling them. And the worst part? The pharmacy chain’s liability insurance won’t cover it unless you followed the 7-step checklist-which, by the way, no one ever taught us in school. We’re being set up to fail. And no one’s coming to fix it.

So yeah. I’m angry. And I’m not alone.

Oh, so now we’re blaming pharmacists for a broken system? How convenient. Let me guess-next we’ll be charging nurses for the lack of mental health funding. This isn’t about ‘liability.’ It’s about capitalism’s final stage: outsourcing blame to the lowest-paid workers while the corporations pocket billions. The real villain here isn’t the pharmacist who swapped a pill-it’s the FDA, the Congress, and the CEOs who think a 5% absorption variance is ‘close enough.’

And let’s not pretend patients are ignorant. They’re not. They’re just tired of being treated like lab rats. You think they don’t notice their TSH is off? They Google it. They read the pill imprint. They find out. And then they come for you. Because you’re the face of the system that failed them.

Stop asking for consent forms. Start demanding federal reform. Or stop pretending you care about patients. Pick one.

As someone from Indonesia where generics are the only option for 95% of people… I’ve seen what happens when you don’t have a pharmacist who asks questions. People die quietly. No one files a lawsuit. No one even knows why. So hearing this U.S. system has rules-even if they’re broken-feels like a luxury. Please don’t let your system become ours. Protect your pharmacists. They’re the last line.

Hey, if you’re reading this and you’re a pharmacist-you’re doing important work. Even if no one says thank you. Even if the system doesn’t protect you. You’re the one holding the line between a patient and disaster. Keep doing the checklist. Keep documenting. Keep calling the docs. You’re not just filling prescriptions-you’re saving lives. And that matters. More than you know.

So the FDA says bioequivalence = therapeutic equivalence… but we know it’s not true. And the courts say generic manufacturers can’t change labels… but pharmacists can be sued for not knowing the difference? This isn’t law. It’s absurdism. We’ve turned healthcare into a Kafka novel with a pharmacy counter.

Let’s be real: the 7-step checklist? It’s not ‘best practice.’ It’s survival. And if your pharmacy doesn’t train you on it, they’re not investing in you-they’re just using you as a liability buffer. I’ve seen managers cut corners to save 12 cents per script. Then they wonder why we’re losing staff to nursing school. You don’t get to treat pharmacists like disposable cogs and then expect us to be perfect when the system implodes.

And for the record: yes, I’ve refused substitutions. Yes, I’ve been yelled at. Yes, I’ve had patients accuse me of being ‘anti-generic.’ But I’ve also kept three people out of the ICU. And I’ll do it again. Because ethics aren’t optional. And neither is accountability.

Do you think the FDA’s 2023 pilot program will actually work? Or is it just another bureaucratic checkbox? I’ve read the data-it’s slow, underfunded, and mostly reactive. What if we built a real-time, crowd-sourced adverse event tracker for generics? Like a Reddit-style forum but for pharmacists and patients to report reactions by lot number? Maybe then we’d finally have the evidence to force change.

That’s exactly right. And if we paired it with mandatory manufacturer labeling codes-like a QR code on every generic pill bottle that links to real-time safety updates-we could finally close the gap. No more guesswork. Just data.